Graphic by Kevin Mobley. Cartoon in the article by Ella Sams.

By KATY MAYFIELD – News Editor

Clarke Central High School teachers and administrators are seeking to counteract current illiteracy and poverty trends with extensive reading initiatives. Will they work?

Senior Jontavius Mitchell doesn’t like to read aloud in class.

“We’ll be reading out loud, then somebody’s reading and they don’t know how to pronounce a word or they read slow or stutter. Some kids always start laughing, they be like, ‘You can’t read.’ Then the other person might get sad and cry,” Mitchell said. “It’s happened multiple times. That’s one of the reasons I don’t read aloud. Because I think somebody might pick on me.”

Mitchell isn’t alone. English department teacher Christian Barner says many of the students in his 10th grade Literature and Composition class are not proficient in reading.

“We do have kids who are reading below grade level, but they’re reading at a ninth grade level. But then you’ve got some kids who are literally reading at a second or third grade level,” Barner said.

The reluctance to read Mitchell describes has become habit for Clarke Central students during the last decade, according to English department teacher Ian Altman.

“Ten years ago when I started, there was not such active and even hostile resistance to trying to read something. There was some, but not like I sense now,” Altman said. “I could assign an on-level class in ninth grade ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ and while they would find it difficult, they weren’t so baffled and confused by it that they would just refuse to read it altogether.”

That aversion to reading, Barner claims, is ubiquitous and entrenched.

“We were doing ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and I did this thing on East Coast versus West Coast rappers and trying to show relations between rivalries and all this, and the kids had to write this fake thing about ‘What if Tupac had a daughter and Biggie Smalls had a son and they were to meet and how would this stuff work?’ And this kid was like, ‘This is boring, I can’t stand this!’ and he was wearing an N.W.A. shirt,” Barner said.

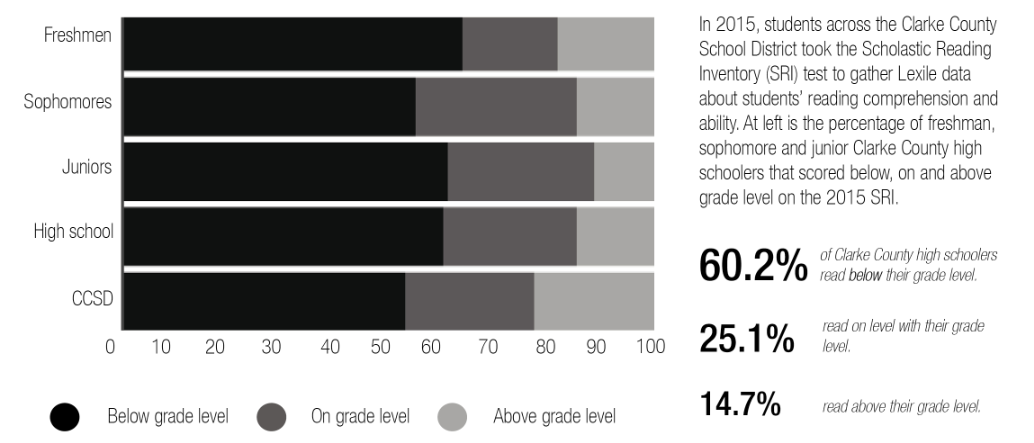

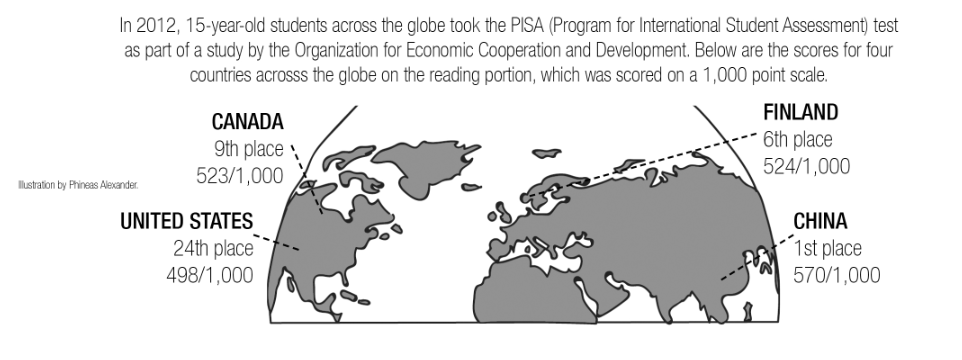

In line with a national pattern of below-average reading scores compared to countries across the globe, students in the Clarke County School District in particular score unusually low on measures of reading ability and comprehension: 60.2 percent of students in CCSD high schools scored below grade level on the 2015 Scholastic Reading Inventory (SRI) literacy assessment, a national reading comprehension test. Approximately 25.1 percent scored on grade level, and only 14.7 percent scored above.

A vicious cycle

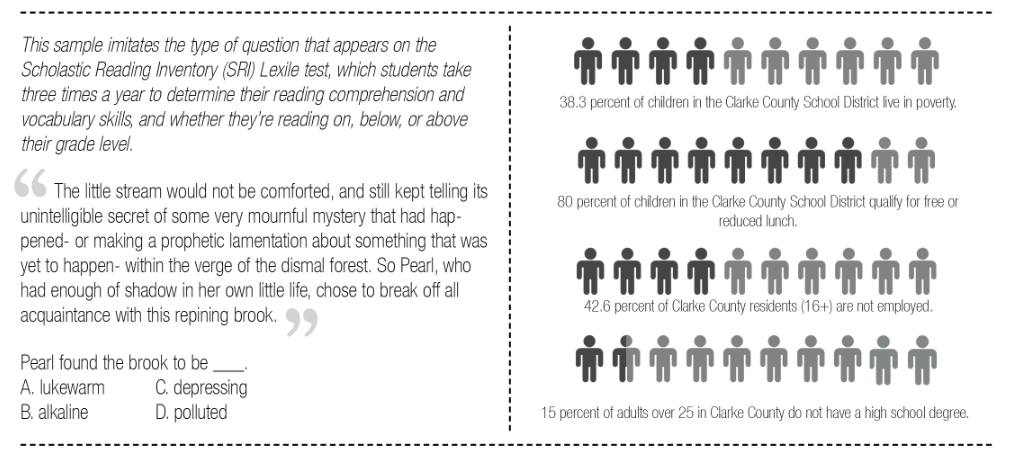

According to the U.S. Census Bureau and OneAthens, Athens-Clarke County’s 38 percent poverty rate is the fifth highest in the nation, with more than one in three Clarke County children living in poverty according to an August 2015 CCSD report for the federal Head Start program.

“The biggest demographic divisions (impacting students’ reading levels) I see fall on socioeconomic lines. Regardless of race and gender and age, there’s bigger divisions between affluent students and students in poverty,” Em Headley, a third grade teacher at Barrow Elementary School, said.

The National Center for Education Statistics came to the same conclusion in a 1993 study, finding adults in the researchers’ lowest band of literacy were “far more likely” than those in the two highest bands to report receiving food stamps, and 41 to 44 percent of all adults in that band were living in poverty.

“I’m a developmental psychologist and my area of research is child development. We have known for a long time that one of the best predictors of kids’ education attainment is parental education level,” Dr. Janet Frick, a CCSD parent and Associate Department Head of the Behavioral and Brain Sciences Program at the University of Georgia, said. “The people who have access to better education make more money, it all sort of snowballs.”

CAPS department teacher Lawanna Knight sees the evidence of poverty’s impact in students who come to school hungry.

“If I haven’t eaten in two days, I’m not worried about reading. I’m not worried about school. In fact, the only reason I come to school is to try to get a couple lunches,” Knight said. “If I’m deprived of food, there’s no way I have enough energy to even function and be able to concentrate and read. I do know there are kids who struggle with that. We see them all the time.”

Home life regardless of socioeconomic status can also have an impact, according to Barner.

“Family can have a lot to do with how you view education,” Barner said. “Think about it. You’re in school seven hours a day, 180 days a year. That’s not that much time. If the majority of your time is spent not (reading and writing) and there’s no value in that, or you come from a home where these things aren’t important, it’s hard to do.”

Such divisions in home life quickly transfer to academic ability during formative years of a child’s education: kindergarten through second grade. By third grade, if a child is far below their grade level in reading, they may never catch up.

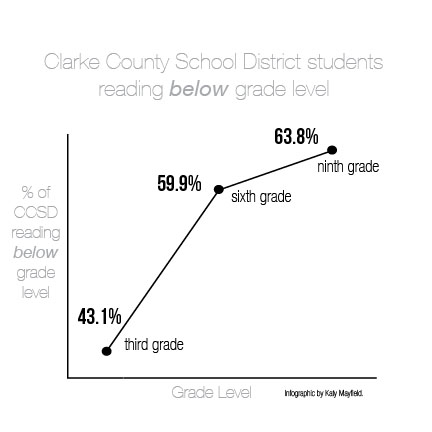

This phenomenon is demonstrated in Lexile patterns. According to a 2015 SRI test, 43.1 percent of Clarke County third graders read below their grade level. By sixth grade that number jumps to 59.9 percent, and by ninth grade, 63.8 percent.

“Half of the people don’t be in class, they just walk around. Then when they get home, they don’t do no homework or try to read or nothing, so it makes it harder to read and be on grade level to read,” Mitchell said. “I have something to do every day, I work and I have a bad memory, so if I have homework, I forget to (read). Other people, I think they’re just too lazy to do it.”

Not many of Mitchell’s classmates read at home.

“I just know one,” Mitchell said.

The standards revolution

In January 2002, a Phi Delta Kappa audit found that Georgia’s previous curriculum system, the Quality Core Curriculum (QCC), which was established in 1985, lacked depth and did not meet national standards for literacy and math.

In response, the Georgia Department of Education replaced the QCC with the Georgia Performance Standards (GPS), which placed more emphasis on comprehension than memorization. Then in 2010-12, Common Core national standards were infused into the GPS to form the College and Career Georgia Performance Standards (CCGPS).

“Kids don’t become better readers because we say, ‘Read this chapter and come in and take a quiz on it.’ That’s not helping them. (Now) the test is something completely different, where they’re testing whether (students) know the standards, not whether they know some detail about the text,” CCHS instructional coach Dr. Linda Boza said. “When we went to Common Core the biggest jump there was that science and social studies and technical teachers had to add that literacy component.”

Though both Barner and Altman support Common Core’s focus on interdisciplinary literacy, both stress the restrictive nature of even those standards which focus on literacy.

“We keep pushing ‘rigorous, rigorous, rigorous, standards, standards, standards, ‘testing, testing, testing,’ and it’s clearly not helping. Then why are we still doing it that way? This whole standards movement, its roots are in the late 90s. If the problem has only gotten worse in that time, then it’s bad theory,” Altman said. “Ultimately, that means students get passed on through without having ever really read much.”

Despite new directives and mandates that come as a result of standards overhauls, Headley insists that her teaching responsibilities have remained steadfast.

“Kids still need to learn, I still have to teach them, there’s still a lot of pressures and it isn’t getting any easier,” Headley said.

Striving to read

In 2006, the Striving Readers (SR) Grant was founded. Funded through an annual discretionary grant from the U.S. Department of Education, the grant is awarded to state departments of education and then distributed to individual schools and counties through a competitive grant process. Applicant schools must be 35 percent or above free or reduced lunch eligible, according to James Barlament, CCSD coordinator of Grants and Research.

“The full name of the program is Striving Readers Comprehensive Literacy Grant, and I think comprehensive is the key word there. SR funding allows schools to make literacy a school-wide focus–not just in ELA or reading classes, but in all classes where the broader definition of literacy is reinforced,” Barlament said.

The SR Grant has one requirement.

“We have to do the SRI test three times a year,” Boza said. “We only had a month and a half, really (between the last two rounds of testing), to see any results. Even with that we still had growth, which was pretty amazing.”

The grant provides schools with $750,000 over the course of five years to use at their discretion on literacy-promoting strategies and materials, like foreign-language magazines, extra books and literacy consultants. Boza continues to spend it per teachers’ requests, buying what teachers say they need to better assist their students.

“I think we’ve improved a lot recently, especially with the Striving Readers Grant. There’s more of a focus on incorporating reading into other content areas, which is huge,” Barner said. “For a long time there’s been the thought that reading and writing is for English teachers, but it needs to be in all these other areas. I’m seeing much more reading and writing and it’s exciting.”

The next chapter

According to Barlament, Clarke Central’s grant funds will last until 2020. However, the federal government recently passed the Every Student Succeeds Act, which may impact SR Grant funding.

“My worry is that the federal funding stream may end, which would end opportunities for additional schools to receive funding in Georgia,” Barlament said.

Looking forward, Headley and Barner suggest more funding and attention directed toward early efforts at literacy, where kids first start to fall behind.

“I would love to see more pre-K classes. Our pre-K is so awesome but there’s lots of kids who aren’t getting in. It’s a lottery system, so there’s a wait list,” Headley said. “I would also love to see more teachers at the K-1-2 level so that kids have a chance to really talk and converse with trained adults.”

To help those kids who fell behind, Barner has teamed up with other teachers and counselors in the building to form what they call the Student Engagement Team, whose purpose is to draw the community into literacy education.

“We have Saturday School, we have after school tutoring. Any teacher will come in before or after school to meet with you. There’s tons of remediation opportunities and ways to get help, but if we’ve got all these kids who just don’t find that value in school, what do we do? To me, that’s the starting point,” Barner said.

Freshman Javier Romero considers himself a reader, though he attributes that passion to parental rather than school influence. On the contrary, Romero believes the school system itself, which he says discourages real literacy, needs to change.

“Little to no people read at home, I think. I don’t think that it’s encouraged very much and that more homework in general is encouraged than just reading,” Romero said. “I think it’s more harmful to encourage (homework) than reading because if you don’t encourage reading then you’re just not gonna use it later in life.”

The apathy and aversion to reading present in Clarke County schools is what Barner says needs to change.

“Kids have been taught that school’s supposed to be about getting a diploma so you can get a job so you can make money,” Barner said. “You can find pleasure in these things, you can find fulfillment in writing and reading and listening to music, a deeper fulfillment, a deeper enjoyment. Listening to a song and understanding these complexities makes the song better. But I guess, again, there’s this disconnect of, ‘How do we get kids there?’”