By JENNY ALPAUGH – Print Managing Editor

“Emanuel is a bully. Stop Rahmunism!”

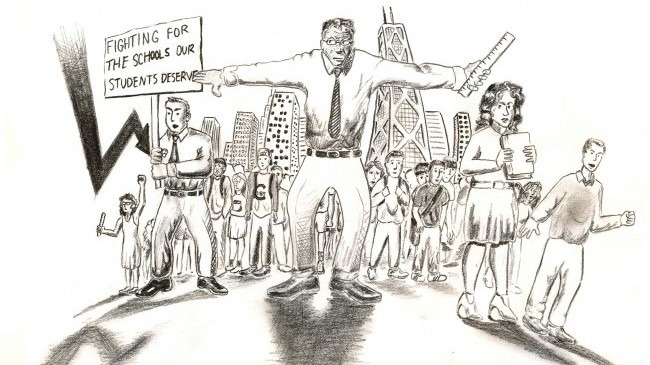

The Chicago Teacher’s Union went on strike for nine days when an agreement about a contract couldn’t be reached. They took a stand to preserve what education should be about: learning. Cartoon by William Kissane.

“Fighting for the schools our students deserve.”

From Sept., 10-19 protest signs with sayings like these, as well as many others, could be found on the streets of Chicago.

During these nine days classrooms were empty, but these weren’t holidays or snow days; the Chicago Teacher’s union was on strike for reasons that hold more than an ounce of validity.

The Chicago Teacher’s Union made the decision to take action when they failed to reach an agreement with Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the school district’s leadership on a contract. The result was the first Chicago teachers’ strike in 25 years.

More than 350,000 students were directly affected by this strike. And hopefully even more students will be indirectly affected, as other school districts begin to reform.

The Chicago teachers were offered a raise of 16 percent over the course of the next four years in the proposed contract.

Chicago teachers are some of the highest paid teachers of the country, according to various reports by the Washington Post, New York Times and the Huffington Post. The average yearly salary lies somewhere between $71,017 to $76,000. Considering those numbers and our country’s current economic state, this raise seems lofty. However the average cost of living in Chicago is 16.9 percent more than the national average according to the 2010 census.

Don’t hardworking teachers deserve it?

These are the people who hold in their hands the education of the next generation. Without them our world would not have made the leaps and bounds it has in the past century. These teachers deserve a decent salary for the important work they do every single day.

But this was not the only reason Chicago teachers were striking.

They were striking against an extended school day.

They were striking to combat the growing dependence on standardized tests.

They were striking to prevent “education reform” credited by those who clearly haven’t spent enough time in a classroom.

It is true that seven days of valuable instruction time was lost. But in the long run, teachers who are satisfied with their contract are more likely to lead their students to success.

And teachers have a responsibility to their students to do just that.

Under the proposed original contract, 75 minutes would be added to make the elementary school day seven hours, while 30 minutes would be added to make the high school day seven and a half hours.

At Clarke Central High School, our day is currently seven hours and 14 minutes long. Students begin to lose focus when in school for extreme periods of time; the added time to the school day becomes pointless if it is not beneficial learning time for students.

Imagine spending an extra 75 minutes at school as an elementary-age student. That’s an awful thought.

Students who are that young need time to be kids. They need a longer break from learning than high school kids do.

The person who suggested this change obviously has not spent much time in an elementary school.

That person was Emanuel. This was just one of his many “education reforms” ideas.

Another change that would ensue, and was also part of Emanuel’s education reform, would be the weight of standardized test scores when it comes to teacher evaluations.

If Emanuel successfully passed the original teacher evaluation plan, test scores would soon count for 40 percent of a teacher’s yearly evaluation.

Standardized test scores are only a small part of student performance. And often test scores are not an accurate portrayal of a teacher’s ability.

Test anxiety may cause students to perform poorly on a test, especially if they know their score might affect the future status of their teacher’s job.

There is already enough pressure to “teach to the test,” instead of teaching students how to be productive members of society.

The Chicago teachers ended up agreeing to enact the extended school day, but they were able to soften the evaluation process when it comes to standardized testing.

They also obtained an average 17.6 percent raise over the next four years, more than originally proposed, but still a far cry from the 30 percent raise for which they were fighting.

For now, the strike has sparked widespread discussion about much-needed public school reform.

But, how long will it be before the strike is forgotten and we are still left with schools in dire need of change?