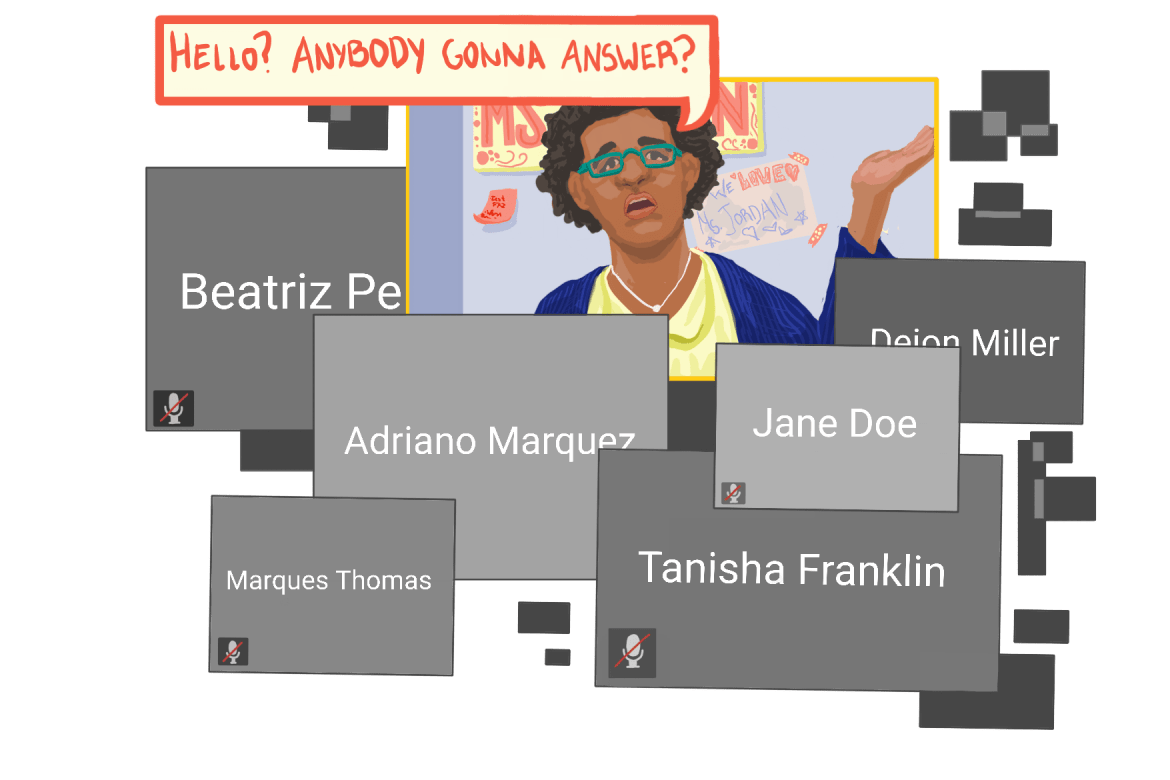

A teacher begs for a response in an online class while students remain silent with their cameras disabled. This has been many Clarke Central High School teachers’ experience with online learning, such as English department teacher Lindsay Coleman Taylor. “I am a teacher who thrives off of the feedback that I get from kids. I feel as though I am a better teacher for them when I know that they are receiving certain information positively, or that they need more because of the way that they interact with me,” Coleman Taylor said. “I’m not getting a lot of that feedback, I’m getting a lot of black screens with names on them, and that’s very difficult to keep smiling and being like, ‘good morning!’ to someone who literally has never spoken. You don’t know what they look like, you don’t know what they sound like, so it’s very difficult to make those one on one connections.” Illustration by Lilli Sams

High school students in the Clarke County School District have participated exclusively in remote learning since March 2020. Students have been expected to show up to four 60-minute class sessions via Zoom every weekday except Fridays.

Along with a new learning environment, virtual classroom expectations have been implemented to better ensure classroom participation. One of these expectations was that students would attend class with cameras enabled.

“Initially, the directive (was that students) should have cameras on. We need to be able to see that they are present,” Clarke Central High School math department teacher Eric McCullough said.

As the year unfolded teachers and administrators discovered that many students were unable or unwilling to turn their cameras on for various reasons.

A student worries over enabling their video in class. Some students have expressed discomfort or anxiety with doing so. Illustration by Lilli Sams

“Then as time rolled on, people brought up concerns of the environment that some of the kids live in. So (now) if they want to turn it on, great, encourage it, but if they don’t, don’t press them about it,” McCullough said.

Some teachers are concerned about the engagement of students who have their cameras turned off in class.

“I have no idea what’s going on behind (my students’) screens. If you’re not showing your camera, you could have walked away, and I don’t really know if you’re there or not until I do a check-in,” McCullough said. “Knowing what’s going on with (my students) and knowing if they’re OK is a challenge.”

For CCHS senior Viki Lee, sharing your face and environment is a personal matter, and is influenced by other students’ participation in the class.

“It gets more daunting (to turn my camera on) because I have self-esteem issues — I don’t like it when people judge how I look. I think this goes for most people. It’s always easier to get people to (enable) their cameras if somebody already has started that trend,” Lee said.

Discomforts such as Lee’s illuminate other issues remote learning poses on students’ mental health, and the CCSD administration recognizes this.

“I know (COVID-19) is real. I know the side effects. I know how they linger. My husband and I had a close family member die, they worked in law enforcement, and they were exposed in a hospital,” CCSD Superintendent Xernona Thomas said. “It’s real, it hurts, I get it. I also get that students becoming depressed is real, students attempting suicide because they can’t connect with friends is real. Students only sitting on a computer all day is real.”

“Student mental health is a challenge right now, just outside of school, just living through this pandemic, and what it’s done to (students) and (their) social life and how that affects you emotionally. Then when you’re in a bad place emotionally, it’s hard to show up for Zoom and do some math.”

— Summer Smith,

CCHS Assistant Principal

Within the school building, CCHS administrators, such as Assistant Principal Summer Smith, recognize the hardships for students living through the pandemic and its relation to their education.

“Student mental health is a challenge right now, just outside of school, just living through this pandemic, and what it’s done to (students) and (their) social life and how that affects you emotionally,” Smith said. “Then when you’re in a bad place emotionally, it’s hard to show up for Zoom and do some math.”

To aid with student mental health, the CCHS administration hired mental health counselor Claudia Ravenell to address student emotional support for the 2020-21 school year.

“We decided to bring on another counselor, which was a very wise idea I think because that counselor only addresses kids who are in crisis,” CCHS Principal Dr. Swade Huff said. “That allows other counselors to support kids with their academic pursuits outside of graduating from Clarke Central.”

As counselors work to ensure students graduate, other staff members are focused on helping families through daily challenges.

“I definitely try to meet the families where they are. As a staff, we have to be on Zooms all day long. I’m exhausted. I know teachers are exhausted. So I get it. I do,” CCHS social worker Bianca Culver said. “Things come up — I’ve been on Zooms where babies are crying, people are yelling, all types of stuff.”

Despite these challenges, CCHS English department teacher Jennifer Tesler has seen some of her students benefit from the structure of online school.

“I think that as much as we need to be together socially, some people do well in an environment like this,” Tesler said. “I have seen quite a bit of productive, good work. It might be because so many kids had that (extended summer) to think about things.”

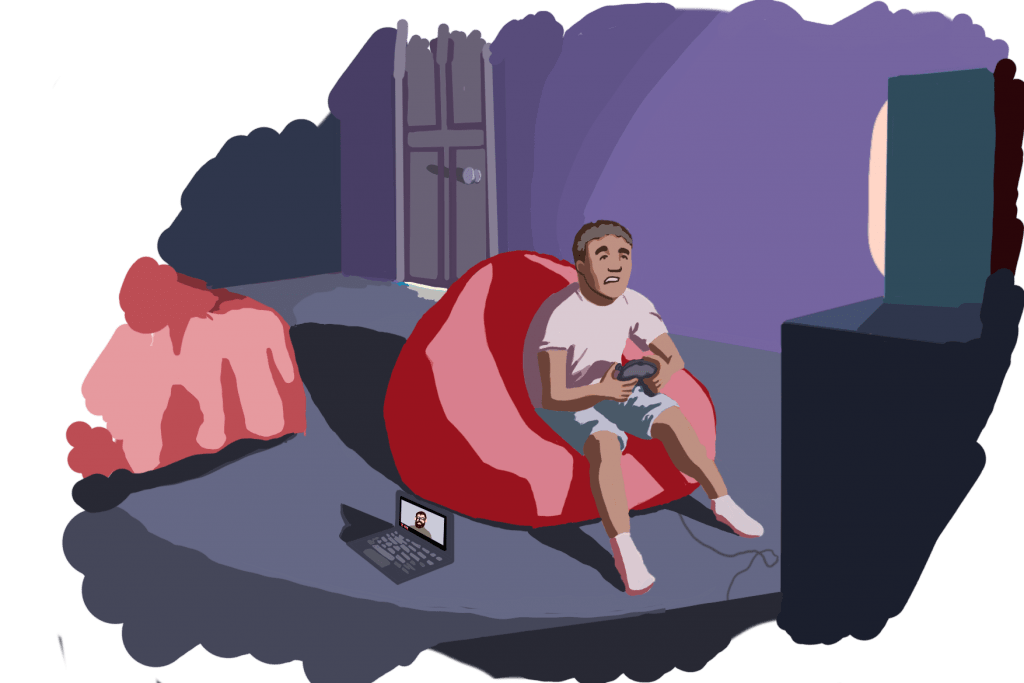

A teenager sits in his room and plays video games while his Zoom class runs in the background. This is the new reality for many students at Clarke Central High School, such as senior Sean Armour. “Online school isn’t that hard. A lot of the time I’ll just put zoom on in the background and just play video games or do whatever. It’s kind of like just having nothing to do all day,” Armour said. Illustration by Lilli Sams

For students like those Tesler has noticed, online school has proven itself as an opportunity to boost grades with a new grading policy that doesn’t allow penalization of late work. CCHS senior Tyrese Harris questions the effectiveness of this change.

“This is like the first time I’ve had an A in English Language Arts. So yeah, I’m liking virtual for sure,” Harris said. “It’s like an easy thing to do. (But) I feel like I’m not really learning. It’s way easier, which is a bad thing because I need to be learning.”

Even with new grading policies, not all students have the tools or means to act out a full education remotely. McCullough has seen issues with technology and Wi-Fi connection among students and has had to work to ensure they received the necessary attention.

“It’s the same five or six kids that I teach that are constantly logging in and out, and it’s just because their connection is going out,” McCullough said. “(I try to be) really understanding (about them having) a bad internet connection, as long as they’re trying to be active and can get the assignment done in a reasonable amount of time.”

In order to combat this, district administration has made efforts to provide supplemental tools to students in order to ensure a meaningful learning environment. However, such resources are not always readily available.

“We’ve ordered hotspots for students. However, they’re back-ordered nationwide, and we can’t do more than that. I know there was talk about (providing Wi-Fi) to all of Athens, and that would be a miracle because we wouldn’t have this problem,” CCHS Assistant Principal Boza Dr. Linda Boza said. “We have students who have Wi-Fi, but it’s spotty. We have teachers with spotty internet just because of where they live. I’ve been in classes where the teacher just freezes.”

When pre-K through eighth-grade classes returned to in-person learning on Nov. 9, 2020, food drop-offs via school bus stopped, meaning families had to travel to receive the meals they normally would have otherwise received at school.

“The parents actually just have to go to certain schools that have the food. I know that has been a barrier for some families. Just last week we had a family reach out and say, ‘I don’t have transportation, and the closest (school) to me is like two miles away, and that’s just not efficient,’” Culver said.

With a tentative return to in-person learning set for March 15 at the high school level, Thomas says her administration continues to brainstorm ways to make this possible.

“There is a team working right now on how we can try to modify what we’re offering for high school. You have to be creative when we can’t use old solutions for new problems,” Thomas said. “So maybe you do half of your day virtually and half of your day face to face, maybe you do a staggered schedule, half of your high schoolers come before the AM and the other half come for the PM. Those are all just maybe’s, but that’s where we are now is really pushing ourselves to be creative in how we approach it.”

Despite school-wide frustrations over the virtual learning space, Tesler sees this era of online learning as an opportunity to reimagine the way that students learn.

“I think this is the perfect time to think outside of the box, to analyze and examine the way that we have traditionally always done school and think about how it could be done differently,” Tesler said. “I don’t know if we are doing that or if we’re just trying to get it done with the same structure in a virtual space, instead of thinking about how it could look virtually in a different way.”