Combating Islamophobia

The Al-Huda Islamic Center of Athens, located at 2022 S. Milledge Ave., is the place of worship for the Muslim community in Athens, Ga. According to imam and University of Georgia professor Adel Amer, the mosque is an open space where community members are welcome to ask questions. “We are one of the communities that’s been kind of targeted in a way and people have questions that we had to answer,” Amer said. “We opened the doors of our mosque to answer all the questions of our fellow Americans.” Photo by Zoe Peterson

In light of President Donald Trump’s recent actions, which have been considered to be discriminatory to Muslims by many, members of the Athens community reflect on the impact of Islamophobia.

On Jan. 27, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that halted all immigrants and visa holders from seven countries with majority Muslim populations from entering the United States for 90 days. Trump’s executive order also banned refugee admissions for 120 days and Syrian refugees indefinitely.

Although this order was called “Protecting the Nation From Terrorist Attacks by Foreign Nationals”, some perceive it to be Islamophobic in nature. According to the University of California Berkeley’s Center for Race and Gender, Islamophobia is “unfounded hostility towards Muslims, and therefore fear or dislike of all or most Muslims.”

“Islamophobia is a phenomenon that people build up through time because of the media, and I would point my finger directly to the media because in the media world, they say when it bleeds, it leads,” Adel Amer, Al-Huda Islamic Center imam and UGA professor, said. “It’s a double-edged knife that has a pretty bad consequences on the societal fabric of the U.S.”

Despite the fact that there has been a temporary restraining order placed on the executive order, controversial pieces of legislation such as this one have brought to light the issue of Islamophobia to communities across the country. Athens is one such community.

“The (mosque) has been here since 1987,” Amer said. “Ever since, the community’s growing and growing and growing, and this is the only mosque in a 50-mile radius. It’s also connected with the MSA, which is the Muslim Student Association at UGA, and it serves all the students that come from different places, like Columbus, like Marietta, like Savannah.”

The Al-Huda Islamic Center of Athens, Clarke Central High School and UGA.

Senior Safwan Bhuiyan, a Muslim, believes it is important to take pride in one’s religion and feels free to practice Islam in Athens, although he acknowledges the fear onset by such a legislation.

“I think it’s very important for people to know that you’re Muslim and you should not be afraid of it,” Bhuiyan said. “I feel a little scared, and I think every person that Trump has targeted is gonna be scared.”

English department co-chair Ian Altman likewise recognizes that the liberal nature of Athens helps to make the Muslim community feel accepted, but believes that lack of knowledge is still a persistent issue.

“I don’t think that Athens, Ga. has quite the same problem that many other communities in the U.S. have, but certainly there is a lot of ignorance here. I mean, I think a lot of people likely don’t know the difference, for example, between Shia and Sunni, and have no idea what Sufis are,” Altman said. “I think that it’s up to not only our Muslim citizens, but also those who support them who honor them for the human beings that they are, to make others aware that they’re not bringing any harm here.”

Despite feeling generally accepted, Bhuiyan recalls instances during which this lack of knowledge regarding his religion translated into offensive actions.

“I remember when my sister was in middle school and I was in elementary school, there was this one kid that pulled her hijab off because — he just went up to her and just like, pulled her hijab off,” Bhuiyan said. “My sister was like, ‘What? I didn’t know people could go this far.’ So, I think she was the most disturbed by it.”

Amer believes that the way to combat Islamophobia is through open communication and willingness to learn.

“We need to build the bridges. We build the bridges, and we ask people to cross the bridge and take the extra mile in order to know, because at the end of the day, I will be an enemy of what I don’t know,” Amer said. “Learning, teaching and education and fighting ignorance is our way to get people to know who we are and what we’re standing for and what Islam’s all about.”

According to Amer, events, such as the open house that took place at Al-Huda Islamic Center on Feb. 4, aid in clearing up misconceptions that community members may have regarding the religion.

“Athens is a wonderful place to live in and people are very understanding and actually, they are very supportive and the evidence is so clear,” Amer said. “We had a wonderful open house. More than one thousand people showed up. It was very successful.”

Bhuiyan encourages members of his community to engage in interactions with one another to build a better understanding.

“I think my community could be more outreached, like going to different community events in Athens to like, help their community. The mosque over there is kinda secluded, so I’d like them to go out and talk to people. Just show them that, ‘Oh, we’re Muslim. We’re good people. Come talk to us,’” Bhuiyan said. “I’m saying, go out, come to the local mosque, and just socialize.”

An American protest

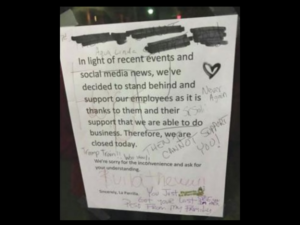

A sign posted outside of Taqueria La Parrilla regarding their choice to close on the “A Day Without Immigrants” boycott was defaced with racist symbols and phrases. Since, it has circulated social media and several news sites garnering mixed reception. Photo by the Athens Banner Herald

Although there were largely positive responses to the “A Day Without Immigrants” boycott, the hateful responses to the protest were extremely disconcerting.

On Feb. 16, the halls of Clarke Central High School were noticeably emptier. There were gaping holes in my classes where people with faces the same as mine usually sat.

They were participating in the “A Day Without Immigrants” boycott, a protest aimed to show President Donald Trump the impact immigrants have as a regularly functioning part of the country.

Although I did not participate due to preexisting plans and a large workload, I stood by my fellow immigrants and was deeply affected by their absences because I realized the significance of the protest. I regretted not taking part.

While at school, I only heard positive things about the boycott, from my first period teacher expressing pride in my absent classmates to a casual “that’s cool” from my non-immigrant friends.

My peers at school were not the only ones who participated. Local businesses like Taqueria La Parrilla in Watkinsville closed for the day as a response to the boycott, and explained closure in a note to customers outside the door.

The next day I found out that people had written hateful messages on the note La Parrilla’s management left, including a swastika and the enthusiastic proclamation, “Build that wall!”

I was at first disheartened, then absolutely enraged.

This was a peaceful protest. The only goal was to show those who might not realize what the country is like without immigrants the sheer weight of their contributions.

A reaction filled with hateful comments such as these made it evident that not only do some members of our community underestimate the value of these contributions, they completely and utterly reject the idea immigrants have the audacity to stand up for their rights.

Messages like, “You just got your last peso from my family,” suggest that immigrant workers are so detached from American culture that they don’t even use the same currency.

This country is founded on immigrants. Our society is the way it is due to immigrants’ countless contributions, dating back hundreds of years. The irony in these hateful comments lies in the failure to realize that.

Our community is no place to make people from different backgrounds feel unwelcome.

To make immigrants feel as if their contributions have no value because they are standing up for what they believe in discourages freedom of expression from a population for whom it is crucial, now more than ever, to take a stand for their rights.

That sounds pretty un-American to me.

Letter from the Editor: Out of many, one

Senior Tiernan O’Neill reacts to the false threats of “anchor babies” from GOP presidential candidates. Cartoon by Ashley Lawrence

After hearing inflammatory remarks from Ted Cruz and Donald Trump, senior Tiernan O’Neill looks back to three words on the seal of the United States of America.

There are three Latin words engraved on the official seal of the United States of America: E pluribus unum. In English, this translates to “out of many, one”.

For many years, this phrase was the de facto motto of the nation, an allegory for the 13 original colonies from which the fledgling country was born.

To me, E pluribus unum means out of many heritages and identities, one America. During British rule, the colonies were a refuge for the ostracized of all kinds Maryland for the Catholics, Massachusetts Bay for the Puritans and Georgia for debtors.

America offered a second chance, a new hope.

This attitude led America to develop into the world’s cultural melting pot. As a child, I lived in Berkeley, California, an extremely diverse community. I had classmates of many different creeds, ethnicities and income levels at school–the melting pot in action.

I often wondered what tied my classmates together, what common thread or experience we shared? How could we speak different languages, say different prayers and eat different foods, but still listen to the same music, learn the same history and watch the same movies?

As I got older, I realized what tied us together. We were all American. No matter what backgrounds we come from, be it Chinese or Zambian, we are all (Enter)-American.

According to the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, no matter where one’s parents were born or their citizenship status, if a child is born in the United States, he or she is a citizen of this nation.

This clause is what allows our country to be the bubbling cauldron of cultures and beliefs that it is. America’s policy of birthright citizenship is what keeps the American identity and dream alive.

It’s the dream that my father had when he spent his all of his savings and flew across the Atlantic Ocean from Ireland. The dream that my mother’s grandfather had when he left his village in the Italian Alps to better his quality of life.

But birthright citizenship is under fire.

Republican presidential candidates, like Donald Trump and Ted Cruz (himself an immigrant), rail against this rib of the American identity, warning of the hordes of “anchor babies” or American-born children of undocumented immigrants flooding our nation. They talk of closing our borders and staunching the flow of immigrants to protect the “American identity,” slowly ripping Old Glory apart.

To be an American citizen is to be a part of something bigger than oneself. It is to be a single thread in the multiethnic fabric of the beautiful patchwork quilt that is the United States. What it means to be American is ever-changing as new threads are sewn in everyday–and that is something to celebrate.