Same race students sit at a lunch tables together, with little diversity at the tables. Graphic by Audrey Kennedy

At Clarke Central High School, self-segregation has the potential to negatively impact connections between students of different races.

When Clarke Central High School freshman Miracle Robbins, who identifies as Black, looks around the cafeteria at CCHS, she sees students gathered primarily in racially segregated groups.

“Everybody has their own little group, but mostly you see White kids with White kids and Black kids with their own group. It’s not really diverse,” Robbins said. “Coming from different middle schools and different (backgrounds), people stuck with their same groups, and then that makes it so (different races) interact worse with each other.”

According to University of Georgia psychology department assistant professor Dr. Allison Skinner, who has done research on how social biases are formed, self-segregation occurs when students are socialized to prefer their own race.

“When (someone) chooses to interact with people of one race and not interact with people of another race, they’re communicating that they’re more comfortable with their own race,” Skinner said. “(That leads to others thinking) that they’re more likely to be socially accepted by people who share their race, and then that’s when self-segregation happens. It’s especially potent in the teenage years, when people think social belonging is a critical thing.”

CCHS freshman Diego Somilleda, who identifies as Hispanic, experiences the effects of self-segregation in his classrooms.

“In my AP Government classroom it’s predominantly White. Almost all of the minorities in that class sit in one corner of the room, isolating ourselves away from the White students,” Somilleda said, “Just take a look at the lunchroom. You sit with people you know, causing you to self-segregate from other groups at school.”

CCHS junior Emily Gaskill, who identifies as White, believes self-segregation takes place due to a variety of factors.

“I notice (self-segregation) in friend groups by interests, which makes sense because interests attract people together in clubs and sports,” Gaskill said. “I do (see it between racial groups), but also I don’t think it’s intentional. I think it’s subconscious. (You see it with) who sits with who and groups in the hallway.”

CCHS Physical Education Department Chair Kasi Carvell sees self-segregation take place daily.

“When students are given ‘choice’ in their activity, they will self-segregate. We will usually see the students group themselves primarily by race and gender,” Carvell said. “The male Hispanic students will choose to play soccer, the male African American students will choose basketball and our female White students will play volleyball.”

Carvell describes self-segregation as when students are more likely to choose to interact with their own race.

“I would define self-segregation as students grouping themselves according to gender, race, ability levels, or with students that (they) already know, etc,” Carvell said. “This can be consciously or subconsciously.”

CCHS sophomore Jonathon Baker, who identifies as Black, believes that self-segregation has negative effects on the way students of different races interact.

“It separates Black people and White and Hispanic, and it really affects us and our interactions with different races,” Baker said. “(At CCHS), the different races just hang out with people of their own race.”

According to Skinner, students are likely to assume that a group of students of their own race will be more welcoming.

“If you’re walking into school on the first day, and there’s one lunch table that has Black kids and one with White kids, (a White student) might choose (the White table) and (a Black student) would choose the Black table, because they might have this assumption that they’re more likely to be accepted by their own race,” Skinner said.

A study from the Public Religion Research Institute, an organization that conducts research about religion and culture, shows that when people socialize more with members of their own race, it leads to a significant social divide between White Americans and Black Americans.

According to statistics from the PRRI study, nine out of 10 of the average White American’s friends are White, and eight out of ten of the average Black American’s friends are Black.

CCHS cafeteria worker Luis Hernandez sees some students self-segregate, but doesn’t believe that the entire student body does it.

“Some people just like to be with the ones that look like them and act like them, and some of them, they don’t. They want something different. It’s just different ideologies about people,” Hernandez said.

CCHS sophomore Wesley Hylton observes students having more friends within their own races, but doesn’t see it as a problem.

“I wouldn’t call it segregation — just people talking to their friends. I don’t think it’s really that serious. I don’t see people saying that they can’t sit at their table ’cause they’re different colors or anything like that,” Hylton said. “Most people have friends that are within their race, but I don’t think it should be a race thing.”

According to the Georgia Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, CCHS is 46% Black, 24% White, and 24% Hispanic. Carvell believes that these statistics can affect how self-segregation plays out.

“We have a wide range of different demographics at CCHS, so it may be more obvious when students do self-segregate,” Carvell said. “On another note, our students also learn to get along and mix with everyone because they are exposed to so many demographics.”

According to Skinner, when different racial groups are close to equal in size it often leads to a more distinct separation of the groups.

“We have done some research essentially showing that biases are highest when groups are closest to being sort of the same size, so there’s lots of friction for over-competing interests,” Skinner said. “There’s the most opportunity for me to see you around and potentially feel threatened by you but not really know anything about you to get comfortable and care about you as a person.”

CCHS assistant principal Summer Smith believes that CCHS’ diversity leads to more opportunities for students to get to know people that are different from them.

“Clarke Central is very diverse. People tend to flock to people that are like them, (who) they know and who they feel comfortable with, but you can still see groups come together in different and odd and beautiful ways. That can’t happen in a school that doesn’t have any diversity,” Smith said. “So maybe we could do some things as a student body to make that more open.”

However, according to Skinner, once a negative bias is formed, the person will subconsciously pay closer attention to things that confirm their bias, making it difficult to overcome.

“If you have a stereotype about a particular (racial) group, if you don’t do something to try and counteract that pretty deliberately, you’re going to subconsciously keep on confirming that bias,” Skinner said. “Kids could see nonverbal signals in terms of one member of a group and a member of another group, and they could learn to favor an entire nationality.”

According to CCHS senior and Black Culture Club member Rosie Sykes, biases affect how students at CCHS socialize.

“When it comes to bias, you are usually going to pick your own race because it’s yours and that’s all you’ve known,” Sykes said. “It can have a negative effect and can just lead you to be so close-minded.”

Baker has experienced the effects of negative racial biases at CCHS in the form of discriminatory comments that generalized Black students.

“Last year I was walking past a girl, and I didn’t do nothing, but she was like, ‘That’s why I hate Black folks.’ I was like, ‘I don’t even know what I did.’ That was pretty offensive,” Baker said.

According to Skinner, one of the most important steps for ending racial biases is extended contact with people from other racial groups.

“We can (move towards solving the problem) by bringing people together and creating some way for them to really value each other,” Skinner said. “Facilitating friendships and close working relationships is going to break down the stereotypes and the assumptions that we might have about other people, and help you form a bond with somebody that you might have otherwise felt uncomfortable with.”

Sykes believes that students should make a continuous effort to socialize with those outside their normal friend groups.

“(We need) more student involvement within extracurriculars, within the classrooms, and the student body overall,” Sykes said.

For Robbins, making an effort to meet people that are different than one’s self is an integral step toward ending self-segregation.

“(You could) start up a club with someone. Just do something that lets you interact with other people,” Robbins said.

Carvell believes that if teachers are deliberate about mixing up students and putting them in groups, it can help to minimize self-segregation.

“I think it may be minimized somewhat by mixing groups for classes, activities, etc.,” Carvell said. “The more knowledge that we provide about different groups- through advisement or other means, the more comfortable students will be with grouping themselves with those unlike them.”

For Somilleda, CCHS’ diverse background has both positives and negatives, but he believes that it can be used to help students stop self-segregating.

“CCHS is pretty diverse with many people from all backgrounds. This is great because it promotes inclusivity, but it also (brings) some unwanted hate and self-segregation,” Somilleda said. “The first thing (we have) to do is talk about it. Bringing attention to the issue will get more people to contribute their ideas to the problem.”

More from Natalie Schliekelman

Evaluating Self-Segregation

Self-segregation within schools deprives students of experiencing diverse backgrounds that allow them to gain different perspectives.

In 1954, following the ruling of the Brown v. Board of Education case from the Supreme Court, schools across the United States began integrating.

Despite the legal integration efforts, a pattern emerged — students were separating themselves by race, an issue commonly known as self-segregation. This can still be seen today at many schools across the nation. Even with a diverse student body, one will often see self-segregation in classrooms and during extracurricular activities.

Self-segregation is counterproductive for students, as it prevents them from diversifying their friend groups, which in turn, limits them to one outlook on life.

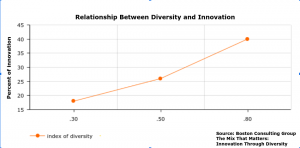

According to a report published by the Boston Consulting Group, being able to understand the backgrounds of others is an important skill that employers will look for in the future. Having such a skill gives people who grew up in diverse backgrounds an important advantage over those who self-segregate.

Students surrounding themselves with a diverse group of people is essential to them developing a good understanding of varying backgrounds and cultures in order to collaborate better with others.

According to a study done by the Public Religion Research Institute, if a White person and a Black person have 100 friends each, on average, the White person will only have one Black friend, and the Black person would have eight White friends. Knowing the statistical unlikelihood of multi-race friend groups shows that there is a real need for action.

The issue is partly due to students’ lack of initiative in developing relationships with peers who look different from themselves. However, the issue is much greater than that. Regardless of students’ attitudes, they will continue to self-segregate because of the lack of diversity in classrooms and the systemic separation of students based on academic achievement.

According to a study done by the U.S. Department of Education, Black and Latino students make up 37% of non-diverse school populations while only 27% make up Advanced Placement classes. Students often have no choice in the group of people they associate with because of the structures in place that segregate students based on “academic proficiency” — which often results in racial segregation.

There are many ways that self-segregation can be combated, but such a solution requires action from school districts, not just the students.

Hiring more diverse teachers and staff for positions at varying levels of course rigor is a helpful solution to provide a less intimidating environment for minority students. Also, introducing initiatives that encourage students of color to take more challenging courses would be helpful to diversify learning environments.

In a study done by assistant professor of education at the University of Wisconsin Scott Peters, called “The Effect of Local Norms on Racial and Ethnic Representation in Gifted Education,” 3.3 million third graders were studied. The study shows that minority students are extremely underrepresented in programs for “gifted” students, with Black students composing only 8 to 10% of the Gifted Program and Hispanic students making up just 3%.

In order to combat this, teachers and administrators at the elementary school level should pay close attention to varying types of intelligence and ensure they are recommending a diverse set of students to the Gifted Program. At the high school level, teachers should take into account the intelligence of their students based on performance, not simply their gifted status. These efforts could likely increase classroom diversity and decrease self-segregation.

Self-segregation is depriving students of an important opportunity to surround themselves with diverse backgrounds that will prepare them for life after high school.