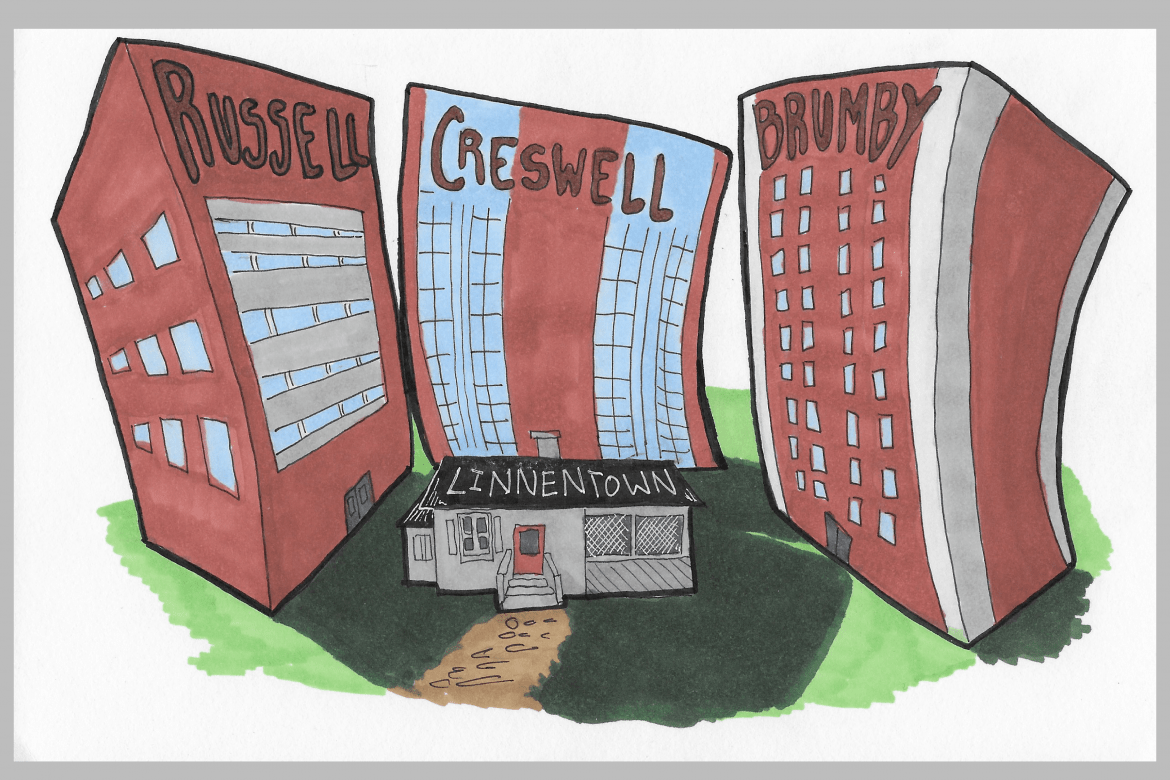

An illustration shows the University of Georgia’s freshman dormitories Brumby Hall, Russell Hall, and Creswell Hall towering over Linnentown. The city of Athens, along with UGA, demolished the neighborhood community under the University Redevelopment Project in the 1960s to build the dormitories. Illustration by Lilli Sams

More than 50 years after the Athens Linnentown community was displaced through gentrification, former residents are seeking support from the city of Athens to gain redress.

Residents of Linnentown, an Athens neighborhood community made up of approximately 50 Black families at its peak in 1960, are now seeking recognition and redress for the University of Georgia’s demolition of their community under the UGA Urban Renewal Program, or Project GA R-50, starting in 1962.

According to the Redress for Linnentown website, the average household income of the neighborhood was $2,000 annually, with occupants owning 66% of properties.

“Without any official name of record, ‘Linnentown’ or sometimes ‘Lyndontown,’ as the community called itself, was a place where Black families were beginning to build up wealth and assets through stable (albeit low-paying) jobs and property ownership,” the website states. “Skilled members of the community included plumbers, electricians, beauticians and brick masons. They were laying bricks for a Black middle class.”

For former Linnentown resident Bobby Crook, the neighborhood had a sense of community.

“(Linnentown) was like a family,” Crook said. “If we see each other at a grocery store or a convenience store (now), we always say, ‘Hey, how you doing?’ And then the first thing coming out of our mouth would be Linnentown, how much we miss Linnentown. Growing up, that’s why it meant so much to me, because that was all I knew. And the people that I knew, I knew them from Linnentown.”

In 1962, however, the Federal Urban Renewal Program granted UGA clearance to demolish Linnentown, declaring it a slum area, in order to build three freshman dormitories — Creswell Hall, Russell Hall and Brumby Hall — in its place.

“The City of Athens has filed with the Urban Renewal Administration an urban renewal project known as the University Redevelopment Project. This project has been developed by (UGA) and the City of Athens under the terms of the housing act relative to college and university urban renewal programs,” a 1961 letter from former UGA President Omer Clyde Aderhold to Sen. Richard Russell said. “This project is extremely important in terms of the growth and development of the University of Georgia. The area involved is West of Lumpkin Street and would clear out the total slum area which now exists off Baxter Street.”

This demolition exemplifies gentrification, a national issue relating to urban planning and its potential effect on certain residents.

“The definitions on it kind of vary, but I think of (gentrification) generally as the transformation of poor working class urban or suburban space into higher spaces for higher income consumption,” UGA Department of Geography student Scott Markley said. “It’s (usually) a combination of the state or government and private interests. It can happen at different paces and at different scales across different cities.”

Residents were forced out of their homes as the University Redevelopment Project was set in motion. Crook remembers the moment this news reached his community.

“I came home and the whole neighborhood is up in a roar. People (were) crying, all the houses down Lyndon Row, Peabody, people were crying and talking, and I was asking my mother what went wrong,” Crook said. “They said, ‘We gotta move. Everybody gotta move. The University of Georgia’s taking our house.”

According to former Linnentown resident and Linnentown historical tour guide Hattie Thomas Whitehead, this neighborhood-wide shock can be attributed to a lack of correspondence between UGA and Linnentown residents regarding the change.

“Our parents did not know what was going on at the time because there were no meetings. There was no communication. There was no assistance to help with moving or transferring or understanding what was going on. Everybody was in an uproar about this,” Thomas Whitehead said.

By 1966, all of Linnentown’s residents had been removed. For Thomas Whitehead, this displacement was detrimental to her family in various respects.

“Long term, it was very hurtful because my family didn’t stay together long after that. My mother and father separated,” Thomas Whitehead said. “The families that we knew, the support systems that we had, were forever gone. We were never homeowners again. My family (had to move to) public housing, which was a slap in the face.”

Since its demolition, former residents of the Linnentown community have not been in touch. According to Markley, this is typical for a gentrified area.

“A lot of times, the former community that was there, all signs of it are typically erased,” Markley said. “It’s actually pretty tricky to identify exactly where (former residents) end up and how they maintain social contacts with the people they used to know from their neighborhood.”

For Linnentown residents, this changed when Linnentown Project Coordinator Joseph Carter heard rumblings of a gentrified community and decided to research it.

“There’s a map from 1918 that shows that area. You can see the two streets that are no longer there — you can see Peabody Street and Lyndon Row. You can see that there (were) houses there,” Carter said. “I pulled the records from roughly 1890 all the way up to 1940, and (from that) you can see that that area grew, sustained, and grew to be a Black community. But that’s all I had. This was early 2019. I started to dig around (the UGA Special Collections Libraries), looking up urban renewal because I had known the general history of urban renewal. That’s when I found everything.”

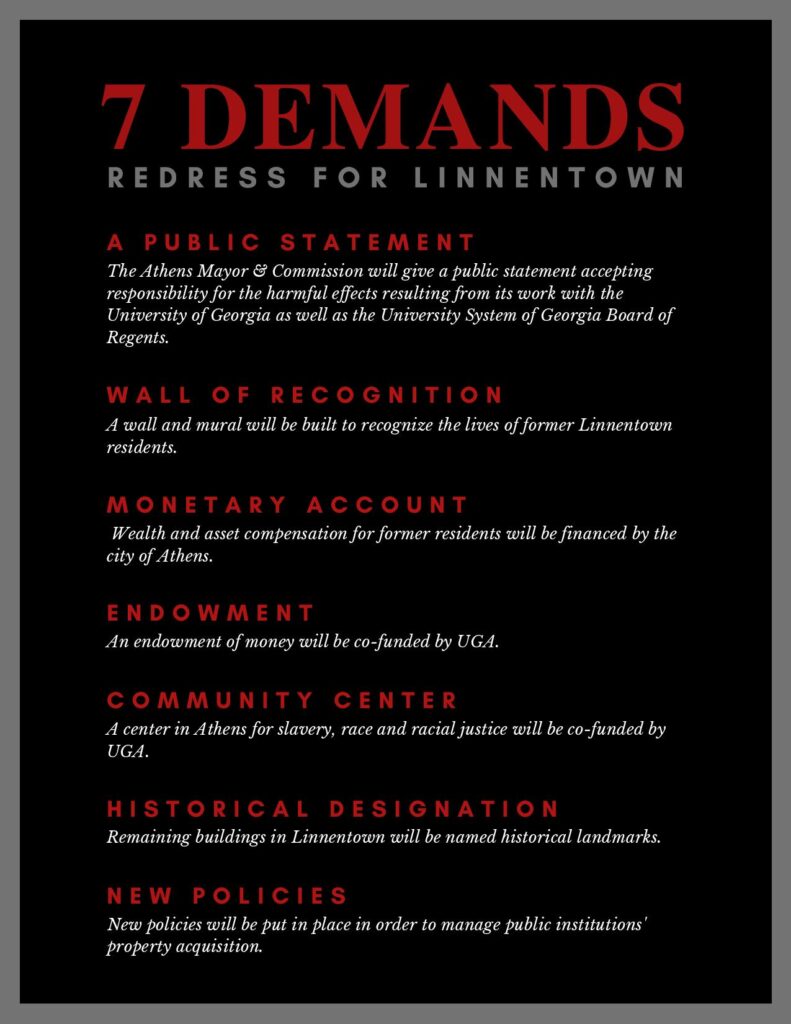

Soon after Carter reached out to former residents, the group set the groundwork for the Linnentown Project. The group is researching the events that happened in Linnentown and seeking seven reparational demands that involve monetary, structural, political and cultural compensation, recognition and redress for the community’s losses under the University Redevelopment Project.

“We’re developing a strategic model called a reparational audit,” Carter said. “The methodology of that audit is to look at historical conditions, policies, budgets and procedures in urban renewal projects, if those are available, to help communities that have been harmed and destroyed, understand what happened to them in ways that they might never have had access to, and then should they choose, to help them organize for reparations.”

According to Thomas Whitehead, this audit will involve the Athens community in what happened in Linnentown.

“I go in communities when communities have meetings to bring an update on what happened (regarding Linnentown). I have been writing different people to ask them to support us. I phone people, I take people on tours (of Linnentown) and I speak publicly about it whenever I can,” Thomas Whitehead said. “I want the community to know what can happen, period, when you don’t stand together as a community, when you have eminent domain or urban renewal to come about.”

As a part of this community outreach, former Linnentown resident Geneva Johnson Eberhart, Thomas Whitehead, Crook and Carter visited Clarke Central High School on Feb. 19 to communicate the story of Linnentown and exemplify speaking out for what one believes in.

“I was very happy that I actually got to come to a meeting like that and see what’s been going on in our town, because our town is very big and so much can happen, and you just don’t even know it. It’s going right over your head,” CCHS senior Kevin Gresham said. “It gave me a sense that I do have a voice and I can be heard, and I deserve to be heard through any situation that I go through.”

For Johnson Eberhart, certain forms of cultural compensation such as a wall of recognition will help bring back her childhood neighborhood.

“What I wanna really focus on is Linnentown to be recreated. On that mural, on that wall (of recognition), it’ll show you where the houses were, the Black children that played out there in the yard and what each house consisted of — what it did, what it looked like,” Johnson Eberhart said.

According to Carter, Athens and UGA’s capability to initiate the University Redevelopment Project was a matter of political power.

“Even though the residents of Linnentown, as Black property owners, could exert a little bit of political power to win an ordinance (to pave certain streets), they still had no power compared to the city and the University because the city ignored the ordinance and went about the plans to seize that land,” Carter said. “The progress (with the Linnentown project) alone and getting the city government to take the resolution and the residents seriously is a first step in helping the residents to gain political power.”

Thomas Whitehead hopes to move forward with the Linnentown Project and achieve settlement for residents.

“If we get the resolutions passed, I think it’ll be a great accomplishment for my descendants and for the descendants that don’t have anyone here to speak for them,” Thomas Whitehead said. “We know that (gentrification) happened, we know it wasn’t right, so let’s get together and let’s reach each other and let’s try to make it right.”