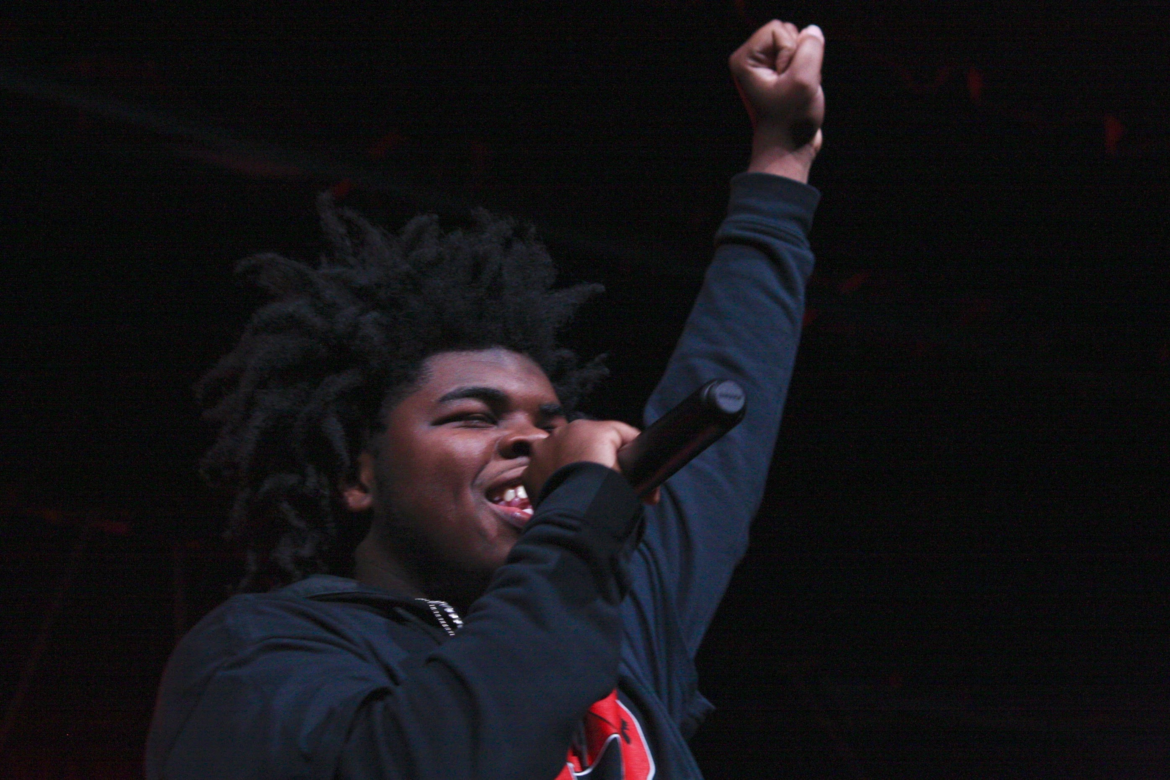

Senior Jeffery Blakely, who performs as Kxng Blanco, performs at the Clarke Central High School Black History School Assembly on Feb. 15. During seventh period, students protested Blakely receiving in-school suspension for the remainder of the day after performing a rap that went off the intended script. “The protest part I was happy to see that people really cared about what I’m fighting,” Blakely said. “The mayhem part with students running in the hallway – a lot of the students, they didn’t even know what they were doing it for. They just saw an opportunity to skip class, and education is important no matter what grade you’re in, so you need to do the right thing, and I do not support that. Nobody who was involved with the protesting part supports that. That was just embarrassing, not only on my name, but on Clarke Central’s name, also.” Photo by Ana Aldridge

Following the Black History Month assembly held at Clarke Central High School on Feb. 15, students protested the alleged censorship of the program.

The Clarke Central High School Black History Month Assembly took place in the Mell Auditorium during third period on Feb. 15. The assembly was emceed by math department teacher Dr. Elijah Swift and included various acts — a Michael Jackson tribute, stand-up comics, a tribute to Black history makers and a rap performance by senior Jeffery Blakely.

Blakely, who performs as Kxng Blanco, drew criticism for his performance by school personnel and was subsequently remanded to In-School Suspension (ISS), which sparked controversy among the student body, culminating in a protest held during the final portion of the school day.

According to an email sent out to parents by Clarke Central High School Principal Marie Yuran after an investigation of the events of Feb. 15, the suspension was a response to a violation of the Clarke County School District Code of Conduct.

“During the program, one of our students performed a rap song that contained derogatory language. As a result of this Code of Conduct violation, Clarke Central High School disciplined the student for a portion of the school day,” the email read.

The email also states the rap performance was in violation of guidelines set for those performing.

“The event sponsors worked closely with students in the weeks prior to the program to ensure that all entries were respectful and free from derogatory content,” the email read. “All student participants agreed to the guidelines outlined by the sponsors. The guidelines included the following: No profanity or derogatory/vulgar references (and) no negative references to any elected officials — including the 45th President of the United States.”

For Swift, guidelines are beneficial in ensuring school functions are free of offensive material.

“When you set guidelines, you have to make sure that the things aren’t offensive to any group of people, and I know that people want to be expressive and share what their concerns are, however, when it offends others you can’t — I know as a school, you can’t just endorse everything,” Swift said.

According to Blakely, the version of the rap he had agreed upon with Black Student Union sponsor Kimberlyn Jackson, a science department teacher, differed from his original idea.

“What y’all heard without the music is what Ms. Jackson didn’t want me to do,” Blakely said. “So, what I did the whole week was rehearse how she wanted me to do it, but I knew when I got onstage, I wasn’t finna do it.”

When requested for an interview, Jackson declined to comment.

Click to view a video of the protest.

According to Blakely, he met with school officials immediately following his performance at the assembly.

“Soon as I got offstage, I got a drink of water. (Jackson) escorted me to the front office. I got in there (and) went to one of the (administrative conference) rooms. It was two administrators and two officers, and basically, we talked. They was like, ‘I’m not wrong for what I said, but I’m wrong for what I did,’” Blakely said.

According to Blakely, the rap he wrote to perform at the Black History Month Assembly covered a variety of topics.

“Part of it was Blacks and minorities need to do better with presenting ourselves to the world like we’ve got some work to do, but we’re doing good,” Blakely said. “And it also just highlighted some points of my life that would usually tear somebody down, but it made me a stronger person. The part that I did do, the original song, the second verse was about Donald Trump and the government.”

In the email, the CCHS administration acknowledged a collection of grievances some students held regarding the nature of the guidelines.

“In working with emerging adults at Clarke Central, the nuance of advising our students to make informed and prudent decisions about their message and how said message will be received is a teaching moment for the student and the advisor,” the email read. “In the translation of the advisement, some students may have felt that their voice was being censored.”

Click to view a video of the protest.

During the seventh period transition, a group of students gathered in protest of Blakely’s placement in ISS. Senior Jalisa Griggs, who resigned as Black Student Union President in response to perceived censorship, addressed the reasons for the protest.

“We, as a small group, decided that during the seventh period transition, that we would go out and start to protest on not only Jeffery’s behalf, but also on the fact that Ms. Jackson, (sponsor) of the Black Student Union, would not allow us to say, ‘Black Lives Matter,’ she wouldn’t let us hold up a Black fist, or discuss our brutal past,” Griggs said.

Jackson declined to comment.

According to English department teacher Ginger Lehmann, the protest was a topic of discussion for students in her Advanced Placement English Language class.

“We did have a conversation about what was going on and we were able to talk a little bit about that and that was actually a pretty good discussion that was taking place with the students that were still in my room during that,” Lehmann said. “So, I think any opportunity to discuss those things can be (a) positive thing.”

However, Lehmann believes that the message of the protest may have missed some students.

“I did hear students chanting, ‘No justice, no peace,’ and I did hear some students referring negatively to the police in a very inappropriate way. But, that seemed to be only a few students,” Lehmann said. “There were a lot of students that I think participated that were using it as an opportunity to behave inappropriately or just to not be present in class. And that to me, can delegitimize the message at the heart of it, that may have been at a good point to make.”

Junior Marissa Goodwin attended the protest and sensed a different rationale between those who protested indoors and outdoors.

Click to view a video of the protest.

“It was peaceful. I liked it because everybody was coming together and they were holding hands, but I think that when they brought the protesting inside, it turned into a different thing because it was mixed in with people who just didn’t want to be in class,” Goodwin said. “Outside, they were speaking facts and truth and everybody was — they were listening. It was calm. And then, when they got inside, they were banging on the walls and stuff, and like, just screaming. It was the people who didn’t wanna be in class, who were skipping, who had no idea, or have no idea what happened.”

For junior Kenya Gresham, the protest was an unnecessary reaction to the events that took place earlier in the day.

“We should all come together when it’s something serious, but over a Black History program that already had rules in place before you went onstage?” Gresham said. “It should not have been taken that far. You had what you could say, what you had permission to do, and you took advantage of it, so you got in trouble.”

For Blakely, the assembly was a platform to communicate issues he considered important.

“I understood that the school’s part of the government, so I didn’t really wanna make it be like, ‘Hey, Clarke County believes this,’ because I know I’m part of the school system,” Blakely said. “I just felt like students, we see this and we know it’s wrong, no matter what race, gender, anything. And we know that police brutality is wrong and I wanted to show that to not only the students but the teachers, also.”

Read the full email here.

Videos courtesy of Connor McCage

More from Valeria Garcia-Pozo