By Louise Platter – Features Editor

In 2010 Kennesaw University student Jessica Colotl was pulled over for a minor traffic violation. Police quickly realized that she had no legal documentation as a citizen of the United States and she was taken to jail to be deported.

“Some people started thinking, ‘How can this girl who is undocumented be a student at a public college?’ They started a very reactionary group and they started to push against educating undocumented students,” University of Georgia Romance Languages professor Betina Kaplan said.

This high profile case triggered an investigation that led to the Board of Regents banning undocumented students from the top five most competitive public universities in the state of Georgia. The ban stated that undocumented students could not attend UGA, Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia State University, Medical College of Georgia or Georgia College & State University.

“There was a group of high school students from Cedar Shoals High School who were undocumented, and because the Board of Regents banned undocumented students from the top five colleges people started to think about access to higher education,” UGA Romance Languages professor Dana Bultman said. “The students asked some interested people in the community for a class.”

A group of professors at UGA who disagreed with the ban searched for ways to fulfill this request.

“The idea of teaching a class came from an activist in the Latino community and we thought that it was fantastic. It was very simple, that’s what we do, we teach, and the students want to take classes,” Kaplan said. “They are not allow- ing us to teach these students, and they are not allowing these students to be taught, so we (decided to) do it outside the system.”

Faculty who were interested in helping decided to materialize the students’ desire for a class.

“It’s always a good idea to find out what people actually need, and so I think it grew out of people who are (high-school aged) making that transition to adulthood,” Bultman said. “If you see that you have certain blocks, one of them being this undocumented status as a Georgia high school graduate, (you want) to find a way to get to college.”

Interested undocumented students looking for a way to overcome the ban were enthusiastic about the idea.

“It doesn’t feel good to watch all your friends get their driver’s licenses and making their college plans and (wondering), ‘What are you going to do?’” Bultman said. “You might be a college bound type of person, and you’re stuck.”

In 2011, Freedom University was founded.

“As soon as we announced it we got lots of students replying to us saying that they were interested in coming to class. We had more than 40 students the first day of classes, so it was a huge crowd,” Kaplan said.

Since then, Freedom University has expanded to accommodate the various needs of students.

“We thought at the beginning that our principal job would be to teach the class, but then we realized that in order to have a class we needed a lot to happen before,” Kaplan said. “We’re now involved in fundraising for everything related to the class and our scholarship fund for students admitted to accred- ited colleges. We figure out the class calendar, what courses to offer, find places to teach the class and recruit volunteers.”

According to Bultman, a major goal of Freedom University is to keep young people intellectually engaged so they can prepare for their next phase in life.

“Freedom University exists as a transition place where people are involved in university level studies, so their minds are active but they’re also being shown how to apply for out of state private places, how to get scholarships, and how to get to college,” Bultman said.

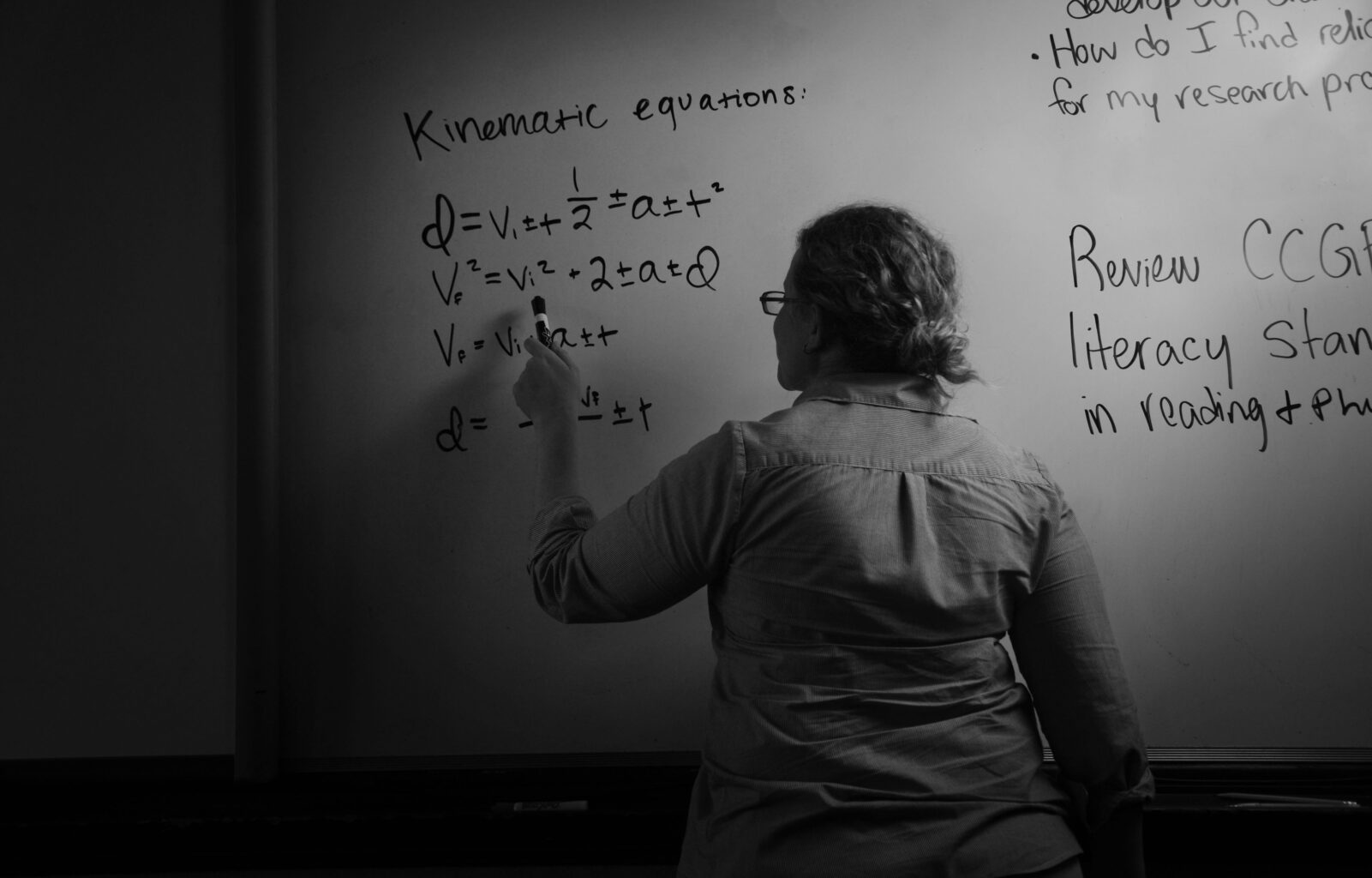

According to Kaplan, Freedom University students are dedicated to learning.

“They are amazing. It’s a big investment for them to come to classes; most of them work all day, and most of them have jobs that are very de- manding physically, so they are very tired,” Kaplan said. “But they still come to class, they come and stay in class for three hours. They are extremely motivated as I haven’t seen in UGA classes.”

Being an undocumented student can be traumatic for young people who feel like they do not have a future because of their legal status. Freedom University seeks to provide a safe space for these students.

“It’s an environment where I felt welcomed. There were people that were similar to me that had experienced similar problems. I immediately con- nected with those people, we were in the same class and we had the same story,” Syracuse University student and former Freedom University student Jose Mosso said. “We were all undocumented, we were all looking for a school and we found Freedom University.”

Although the program has been in existence for three years, UGA professor JoBeth Allen said that many still do not know Freedom University exists.

“There are still people who are unaware of the ban on undocumented students, and when they hear about it they are generally appalled,” Allen said. “Of course, there are people who think it’s the correct policy, but there are people who are unaware of the policy, and unaware of Freedom University.”

Despite the sometimes negative reactions, Freedom University continues to provide for students who are trying to make a life for themselves in the country that they have grown up in.

“(If I hadn’t found Freedom University,) I would be back in Georgia still working in construction. Before I moved, I was working in construction so that’s where I would still be. Freedom University was my way out, they helped me find an education,” Mosso said.

Students who wish to attend Freedom University — either upperclassmen in high school or already graduated — must fill out a simple application on their website.

“It was a very basic application process. They asked me why I wanted to go to school, when I graduated and simple essays. That’s how I started get- ting involved,” Mosso said,

Despite the obstacles, Kaplan believes that the students who attend Freedom University are exceptional in their commitment to overcome the restrictions placed on them.

“They know why they are in class, they have a clear idea of what is at stake for them if they don’t get a college education,” Kaplan said. “That makes them more aware of why they want to study and they are very focused.”

More from Louise Platter