By HANNAH GREENBERG – News Writer

The Clarke County School District assists homeless children living in the district in securing a successful education.

Having a place to call “home” is not guaranteed for all children — homelessness is a growing problem for students in the Clarke County School District. Katie Wheeler, Homeless Education Program liaison and school social worker for the CCSD, has seen this increase during her time working for the district.

Photo by Carlo Nasisse

“My first year at this job was (the) 2008-09 school year and I had about 270 (identified homeless students) on my case load, it was upper 200. Ever since then I’ve hit 300 at the end of the year,” Wheeler said.

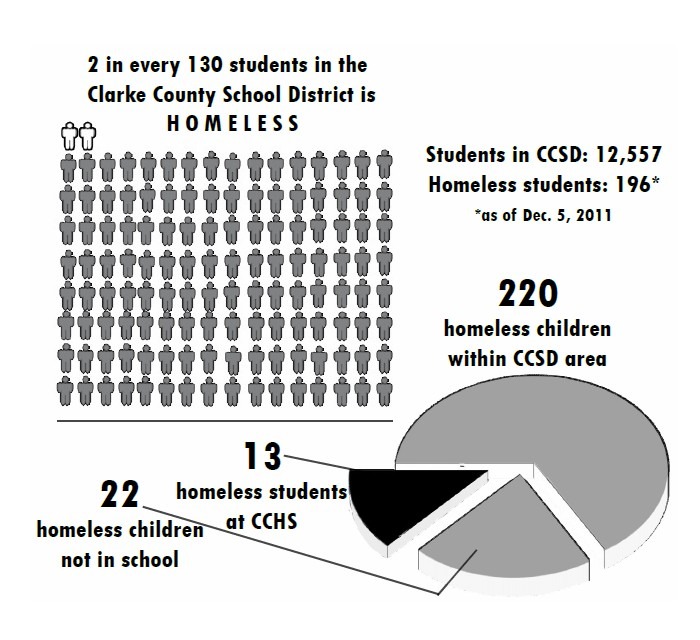

Currently there are 196 identified homeless students who attend CCSD schools, with a total of 220 when homeless children who are too young to attend school are included. In the spring, the number of identified homeless students in the CCSD is expected to be about 350. The CCSD has taken steps to begin to solve such issues by instituting the Homeless Education Program in the early 1990s.

Clarke Central High School counselor Lenore Katz makes sure that homeless children are aware of their rights by introducing them to the HEP.

“We make sure that (all homeless students) feel like they have some stability in their lives, so that they can concentrate on what they are (in school) for, which is go to their classes, do their work, get their credit and get their high school diploma,” Katz said.

The HEP, based on the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, reauthorized in the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, defines being homeless as, “unsheltered or (living) in shelters, domestic violence safe houses, transitional living shelters, motels, camp grounds or vehicles.”

Unaccompanied youth — children who do not live with their legal parent or guardian — are also considered homeless along with children waiting to be placed in foster care. There is also a “doubled-up” circumstance where families, unable to provide for home of their own, are forced to live with another family or person.

“The way that (the McKinney-Vento) law is written is that if you are identified as homeless, even for one day, then you remain as such until the end of the school year,” Wheeler said. “Homelessness is a chronic issue; if you are homeless today you are likely to become homeless again later on. Many of our families might get housing and then within a few months might lose that housing and be homeless again.”

Homeless students are certified to exceptional rights. When enrolling to a new school they are not obligated to present all of their records. Out-of-state students have 90 days and in-state students have 30 days to submit these documents, which can be received and processed by Wheeler.

“(The CCSD) is very understanding. As far as (the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act) goes, we cannot impede a child’s education based on a piece of paper,” Wheeler said. “Even though they have 90 days, and it has to be done by then, that child will not sit out of school because we don’t have an immunization form. Our staff and school nurses are all very aware of that and they are very helpful when it comes to that kind of thing.”

If a family is forced to move to a different schooling zone due to homelessness, the student is allowed to continue attendance at the school in the previous zone. Transportation is provided to these students.

“You can remain at (the school) as long as you qualify (as) homeless, if that extends over school years or to the end of that school year. We get bus transportation for those students to get back and forth across town,” Wheeler said. “So, although, there might be a lot of inconsistencies outside of school, at least your school day will remain consistent.”

Graphic by Caleb Hayes

The HEP is able to provide several other services in addition to transportation. The CCSD receives grant money from the Georgia Department of Education, used to fund the purchase and facilitation of school supplies, tutors, after-school programs, emergency supplies and toiletry items to homeless students. Awareness material, such as posters and information folders, are also purchased with this money.

Another service the CCSD provides is a possibility for children living at shelters to participate in story-telling activities.

“We fund a story-telling program at the shelters. It is a partnership with Athens Regional Library. A retired Clarke County School District teacher goes to three local shelters one night a week. She does literacy activities like crafts, story-telling (and) music,” Wheeler said.

At CCHS the counselors work to ensure that all homeless students are informed about their rights to receive services.

“It’s a big challenge because people don’t realize that it doesn’t have to mean that you are living on the street in order to be eligible for homeless education services,” Katz said. “We have things around the counseling office that are posted so that people will know.”

Emily Smith*, a senior attending school in the CCSD, has been living at a local shelter for about a month. Before moving there, Smith lived at five different locations. Living by herself at a shelter, Smith classifies as both unaccompanied youth and homeless Smith appreciates the assistance she has received from the CCSD.

“(The CCSD) helps you graduate school. They help get tutoring after school and they help you get clothes (and) food,” Smith said.

When coming in contact with homeless students, Katz refers them to Wheeler. Katz stays in contact with the students to offer help if needed during their time at CCHS.

“My job as a school counselor is to make sure that (the students) feel back in control of their lives again; that someone is there to help and that they’re not alone — because that’s all any of us needs,” Katz said. “When they leave my office the goal is that the feel that there is a plan and that everything is going to get better for them day-by-day.”

*The student in this story agreed to participate only under the use of a pseudonym to protect her identity. Therefore, she has been given the name Emily Smith.